Unique Culture

Shooting the Shima

Amami Archipelago Reminisces

I documented the Amami archipelago in photographs during 4 stays in the region from 1955 to 1957 that totaled 182 days.The opportunity came to me as a member of the joint investigation team of the Kyuu-Gakkairengo at that time.The Kyuu-Gakkairengo is an academic society of 9 organizations in the humanities, archeology, linguistics, religion, nation and peoples, folklore, sociology, psychology and geography that all research human life studies through field work.One sharp, young researcher in the group taught me what documentary photography in the context of sociology was as I made the Amami archipelago the subject of my study.The microfilm I shot in the span of 3 years exceeded 17,000 microfiche that remain stored in Haga Library.The shooting did not go smoothly at all during the first year.To islanders, photography meant taking souvenir photographs on auspicious days, like weddings and graduations when everyone looked their best.Many were ashamed of being shot in their dirty work clothes by a cameraman from the urban part of the country.

Wherever I went and no matter who I spoke to, the conversation first started with persuasion and an attempt to get consent that wasn’t easily had.

When Mainichi Shimbunsha published the photos in the Amami no Shimajima collection in 1955, followed by Sango no Shima photo collection Heibonsha Publishers released in 1956, these records of daily island life were addressed in a meeting of the Diet. This spurred a movement for the Act on Special Measures for the Amami Islands Promotion and Development, and acknowledgment on the part of the islanders on the impact of documentary photography.

Looking back now on the photos of island life at the time, every single shot is a history of the degree to which the social infrastructure of Amami was off the radar of the government of Japan.

Amid a severely bitter situation, the shots depict people in the islands working to care for their aging parents, raising children and praying for their islands to be returned to their native Japan.

The greatest scene of the time was in a group of storehouses in Yamato-son, where you could hear workers singing typical songs.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing left of that scene now.

The biggest route of transport through Taken village in Uken-son was a single creek and zero paved roads.

The only in-island transport on Tokunoshima was a converted Jeep left behind by US Forces.

At low tide, boats couldn’t reach the wharf in Wan village in Kikaijima, so the islanders built wooden piled jetties by hand to add to it.

There was a solid fresh water spring in Azefu village in Wadomari-cho on Okinoerabujima, but none of the houses were connected to it by pipes.

On Yoronjima, steamers passing the island without stopping was a frequent occurrence.

I’ll never forget the figures on the wharf lamenting and shedding tears each time it did, remaining standing until they were exhausted.

Grouped storehouses in Yamato-son, Amami Oshima (1955)

This was the largest scale of storehouses in Japan.

You can still hear the songs people sang as they worked.

The scene is gone now.

Fresh water spring in Wadomari-cho, Okinoerabujima (1956)

A bountiful fresh water spring in Azefu village, Wadomari-cho.

People and cattle both bathed there.

They say females bathed on moonlit nights.

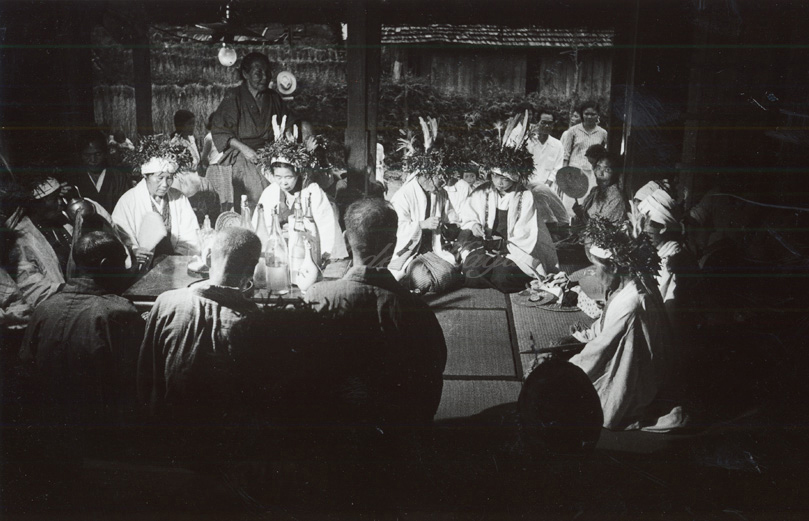

Arahobana

Arahobana

On July 28, 1955, I was unexpectedly taken by the arm to the noro*1festival Arahobana in Daikuma, Naze-city (current Amami-city).

I was part of the Photography group for the Kyuu-Gakkairengo joint investigation team.

Ignorant of the meaning of the scene before me, I saw young girls, their hair adorned with beautiful white tail feathers and Stag’s-horn clubmoss, dressed in the white robes of noro shaman and wearing necklaces of crystal beads.

An assistant ukkan aided the noro shaman in dipping the tip of an ear of rice in sacred sake as she performed a ritual to pray for good harvest.

11 women in the role of igami flanked the noro’s sides as 2 male gujinushi and three village headmen sat opposite the shaman.

The women began to worship by singing omoro*2 in chorus.

As I listened for over 20 minutes to their singing, I was amazed that Amami women infused everyday life with such thriving tradition.

Arahobana

*1 Female shamans who were commissioned to perform public rites, rituals and festivals during the Ryukyu Kingdom era.

*2 Omoro/ Ancient songs passed down in the Okinawa and Amami archipelagos

Horse of Kikaijima

In July 1955, a steamer arrived at the wharf in Wan, Kikaijima from Naze-city (current Amami-city).

It was headed to Araki hamlet.

Just as it got close to Nakazato, there appeared a horse-riding lady gallantly racing her animal.

The horse was bringing along a cute pony.

I hear that Kikaijima is well-known for horse-breeding.

This must have been one of the kyaa-ma, or Kikai horses.

There were roughly 3,000 heads in the Amami archipelago at the time, 1,700 of which were on Kikaijima alone.

To both plow rice fields and press juice from sugar cane, horses put out 3 times the strength of a person.

But kyaa-ma fed as much as they wanted on pastures of rising coral reefs that grew green grasses full of calcium and other minerals that made their bones thick and strong.

One farming method used on Okinoerabujima allowed horses and cattle to freely roam and pasture in rice paddies where water was drawn.

In a process known as fungomi, the soil was effectively tilled as cattle and horses walked on it, and fertilized by the animals’ defecation.

Once mechanical cultivators, chemical fertilizers and pesticides became available in the years after 1956, horses were no longer chosen for the task.

Kyaa-ma are now extinct*1, and there is now only 1 foreign-bred pony and 2 Tokara horses in Kasari-cho.

There are probably a lot of children nowadays who’ve never seen the former hard-working horses of Amami.

*1 The Kikai horse stands between 100 and 120 cm (39.3 and 47.2 inches) tall.

Tolerating heat well, the animal was used to plow fields and as a charger.

The modern Tokara horse that is a Kagoshima prefectural natural monument in the role of Japan's common horse is a descendant of the extinct Kikai horse.

The Kikai horse was introduced to Takarajima of the Tokara Islands in 1955 for breeding, but the animal was named Tokara horse at its discovery in 1952 because the Amami archipelago was under administration of the U.S. military forces at this time.

(Horizon Editorial Office)

Horses in Kikaijima / Umuge-e work saddle can be seen on the straw mat over its back.

Note the characteristically Kikaijima-style headstall.*

(This species of Kikai horse is believed to have both thoroughbred and anglo-norman blood. (according to veterinarian Yoshitaka Kosaka)

Fungomi of Okinoerabujima

Feast of Hama-ori

It took place when I visited Inokawa in Tokunoshima on August 15, 1957.

It’s a gathering of each hara*1 that starts at dusk.

The elders of the hara first stand a single log on the shore.

The log becomes the base for a pot that is built using corallite from the beach. An offering of a plate of food and sacred shochu spirits is made to the ancestors as people solemnly pay respects to them.

On the beach, each hara built a small hut of simple bamboo poles called a hamayadori, in which seats for the men and seats for the women were then prepared.

Each household brought handmade gourmet dishes in stacked lacquered boxes from their home to share and eat together, potluck-style.

Everyone’s lacquered boxes were distinctly “ichijyuu, ichibin“.

So each house had a different flavor to its dishes.

There was no end to the feast: pork simmered in miso, fried fish cakes, boiled fish-paste, vegetable tempura, fried fish, white rice, rice with red beans, and pickled vegetables, just to name a few.

Even if the food looked the same as that from another household, you could taste the difference when you tried each of them.

That was the fun of the ichijyuu, ichibin way things were done.

Youth sat politely on their knees in front of one elderly lady, bowed, and drank shochu from the single glass they received until it was completely gone.

The shochu this lady brought with her was an especially flavorful, well-cured spirits known for its great taste.

I’ll never forget how it tasted, either.

Here’s hoping that Amami’s wonderful ichijyuu, ichibin (singular box, singular bottle) custom lives on.

It’s truly a magnificent traditional culture.

*1 Word that expresses kinship by bloodline in the Amami archipelago.

In Kikai and Amami Oshima, hiki is used, while hara is mostly used on Tokunoshima and the islands southward.

Hama-kudari in Inokawa, Tokunoshima (August 15, 1957)

All households fill stacked lacquered boxes with prepared food and fill cups to the brim with shochu according to ichijyuu, ichibin custom.

Kuragou of my youth

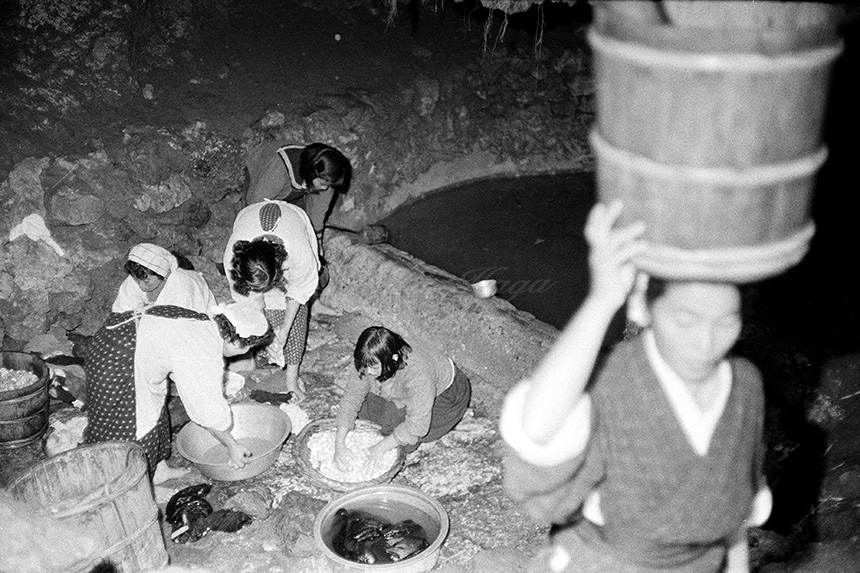

On the Amami archipelago islands with coral reefs (Kikaijima, Okinoerabujima and Yoronjima), there is nothing on the map like a river, where water is constantly flowing.

Although it receives nearly twice the rainfall of Tokyo, this all ends up being absorbed by the surface.

These kuragou become springs that spout forth from the bottom of dark holes and flow to the ocean.

People who lived in island villages from 1955-1964 drew this water to use for daily life.

Older girls or young wives had the role of going to draw water.

A large bucket or cask would weigh 10 kg or more when full of water.

The girls and women would skillfully balance these on their heads to carry as they climbed wet, slippery rock steps and then navigated wooden planks laid on the paths to their homes.

Some young mothers even carried water with babies strapped to their backs.

Since they needed both drinking water as well as water for bathing, girls and women would go down to the kuragou 5 – 6 times each day.

Island wives who could not haul water with skill would not have any men who were willing to marry them.

Girls were taught from the age of 3 – 4 how to carry items on their heads.

Women carrying water on their heads as they mount wet steps at a kuragou in Sumiyoshi village, China-cho, Okinoerabujima.

Island ladies who laundered are drawing drinking water at a kuragou in Wadomari-cho in Okinoerabujima.

Their voices were unexpectedly bright and perky.