Column

Nobori Shomu

昇曙夢(のぼりしょむ)

Nobori Shomu

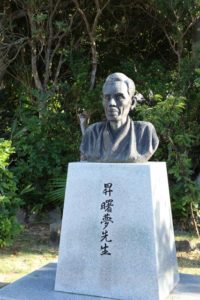

In a village with gently rippling waves on Kakeromajima, there is a park that has a bust of the first Russian literary scholar, Nobori Shomu. What was the connection between this fishing village on a remote island and Russian literature? As I read the inscription, I followed the life steps of this literary giant.

Nobori Shomu (whose real name was Nobori Naotaka) was born in 1878, the year following the Satsuma Rebellion that occurred in Shiba village, Kakeromajima. After he graduated from Oshima higher elementary school, Shomu took a test to enter Kagoshima Normal school, but failed. Helping out in the bonito fishing business of his hometown, he spent his time in despair.

Later he met a religious follower of Greek orthodoxy who was a friend of his elder brother. Shomu’s life goes on to change dramatically. Feeling he had been given a revelation by the follower, 16-year-old Shomu overcame the deniers around him and entered the Nicolas Orthodox Church School in Kanda, Tokyo after his baptism in Kagoshima. As he lived in the dorm for seven years, he learned everything in Russian except Japanese, kanji, and math. Also, he had learned Russian literature and philosophy better than the faith.

In the year the Russo-Japanese war started, Nobori Shomu published “The Great Russian Writer, Nikolai Gogol (Rokoku Bungō Gōgori).” His pen name was taken from one of the poems in a poetry anthology by Uchimura Kanzo, whom he admired. Shomu met the Russian literature translator Futabatei Shimei when he published the book, and started writing Russian translations and critiques. Information and literature of Russia quickly gained attention during a time known as the “Nobori Shomu Era.” He played an important part in journalism after Futabatei Shimei died at the age of 45.

Shomu translated literary masters like Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky and up-coming realism works. “Every time his work was introduced and was published, people were arguing. But his work gave off a feeling of freshness,” said famous novelist Mushanokouji Saneatsu. Shomu significantly influenced young literary men like Akutagawa Ryunosuke.

Politically-pressured and suffering, Russian serfs looked like Amamians to him. He brought enormous passion into the study of Amami into works like “History of Great Amami (Dai Amami-shi),” and others. Shomu worked on lyrics for new folk songs as well. During the movement for reversion of the Amami archipelago, Shomu held successive post as a national chairman in the Amami Union. He greatly contributed in spite of being ill at the risk of his life.

In his 1955 culmination, “History of Russia: Soviet literature”, Shomu received an award for the Prize of the Japanese Academy of Art, and Yomiuri Prize for Literature. He had closed his life to outside turbulence by retreating to his home in Kamakura at the age of 80. Sixteen years later, the bust was built in his hometown to commemorate him as a great historical person. Shomu’s soul left home to become a Russian literarian, published about 180 books, and now gazes at the sea of Neriyakanaya.

<Monument data>

Height: 90 cm (approx. 35 ft.)

Seated atop granite. Donations exceeded six times the anticipated goal.

The sculptor was Amami native Motoi Shuntaro.

<References>

Tashiro Soichiro, “Genkyo no Amami: Roshiya Bungakusha Nobori Shomu to Sono Jidai” published by Shoshikankanbo, 2009.

Nobori Shomu, “Kanreki Anniversary Rokuninshu to Doku no Sono”, (translated by Nobori Shomu), published by Seikyojihousya, 1939.

Kato Yuri, “Meijiki Rossua Bungaku Honyaku Ronko” published by Toyoshoten, 2012.

Posted on Minami Nihon Shinbun ”Southern Kyushu Bungaku no Ishibumi(Monument of Literiture)” April 3rd, 2022