Island of songs

What is Amami’s Shimauta

Amami’s Shimauta

Shimauta and Song Play

The Japanese word shimauta was born in Amami, and while there is strong evidence that it was passed on to Okinawa too, we can say that it has been used with a vague definition in Okinawa as well as Amami.

The term shimauta sometimes refers to the entirety of island songs even in Amami, as the meaning of the term suggests. However, in most cases, the word is used to indicate songs sung to the accompaniment of shamisen in a kind of “song play”.

Spirituals, August songs, work songs, play songs and children’s songs

All other songs are called by different names. The songs of those noro and yuta who engage in spiritual activities such as praying for the safety of the village and for purification for individuals are known as spirituals, kuchi, or omori. The hachigatsuka songs in which men and women sing short verses in call-and-response style as they dance Hachigatsu Odori are the songs most closely related to shimauta in its strictest definition.

Former work songs, like the rowing songs and planting songs sung when on the ocean or in the rice paddies, and the weeding songs when in the fields were mainly called ito, or calls to time or encourage some form of labor. Most of those forms of labor have now disappeared, and the ito have changed to use in song play to the accompaniment of shamisen. And the genre is full of warabeuta children’s songs. They’re uncountable if the songs sung at seasonal events and performances such as Shodon Shibaya and Yoron Jyuugoya Odori are included in the number.

Faith apparent in asobiuta play songs

The fun songs of asobiuta (also known as utaasobi, or song play) surely form the core of shimauta. The activity can be thought of as “songs sung to play” as well as “the act of singing and playing”: both definitions describe it well. But the word asobi (play) as used here included a much broader range of meaning than is used today, and included hints of religious significance as song and dance performed as an offering to the gods. While the element of entertainment is of course in all shimauta, but it certainly also includes purification of a place, and a sense of everyone having come together by divine will.

Shimauta: fortune of the village

One critical point that must be remembered is that the word shima in shimauta refers not only to the geographical landmass, but in Amami to “the village in which one lives”. In short, uta-asobi itself has always taken place at the village level, and each village considered both the lyrics and melodies of these having been each village’s inheritance in the past.

They say that if you went to some different areas and tried to change the melody of the tune, you would even be scolded. On that point, modern singers (utasha) can now even freely promote their uniqueness beyond the boundaries of their village. Things have modernized in a sense.

Origin of the shamisen

The primary instrument that accompanies shimauta is called by several different names, including sanshiru, samusen and sanshin, but they all refer to the shamisen that spread to Okinawa from China in the mid-14th century. It’s known for certain that the form of the shamisen first in introduced in Okinawa retained almost the same shape as the Chinese shamisen, and eventually reached Amami. Before that time, the taiko was the main instrument in Amami and Okinawa. From a musical standpoint, the shamisen can be called both a melodical instrument even as it is a rhythmical instrument to replace the taiko, especially in Amami. Rhythm is considered very important there.

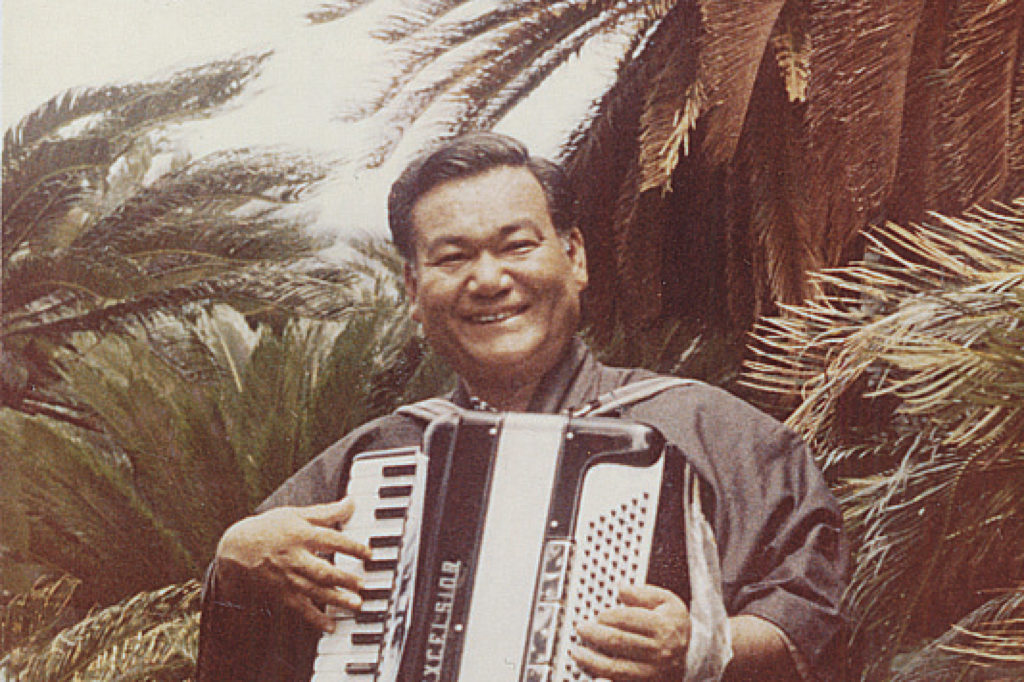

For the longest time, the shamisen was an instrument to be played only by men because it was first introduced in the Ryukyu dynasty. In more recent times, many women have taken up the shamisen as they sing and shimauta itself has evolved significantly as a result. And since a woman held the shamisen, she could sing at a pitch as high as she likes, and at which a man might not be able. The end result was that the call-and-response form that was the most attractive part of shimauta became more difficult to perform.

Verses set to Ryukyu tunes

Most shimauta are short song lyrics in verse form set to 8886 meter, referred to as Okinawan fixed form poetry. The influence of Okinawa (formerly Ryukyu) seems apparent from the name.

But further research reveals that there are even more songs of this verse form in Amamian shimauta. You’ll also find nearly as many mainland-style forms as there are Okinawan. One has ballad-like lyrics in the 7775 meter of early modern times, and is the form in which Amami’s distinctive hand-flutter dance Rokuchou is written. Even the

The 75757575 meter that frequently appears in the late Heian era song collection Imayou exists in multiple adaptions in the shimauta genre. Ikyunnyakana Bushi, categorized as one of Amami’s “counting songs,” is an example.

Prominently Japanese musical scale

An issue in terms of musical scale is that in Okinawa, the Okinawan scale, which completely differs from that of the Japanese mainland, is the main scale used, and this influence is strong in the songs of Amami islands Okinoerabujima and Yoronjima as well. An Okinawan-tinged scale sometimes can be heard in northern Amami as well, but musical scholars say that the Japanese pentatonic scale and anhemitonic pentatonic scale (folk scale) is primary.

Origin of Amami’s distinct falsetto

The falsetto, a particularly unique feature, is not seen either in Okinawa or the Kagoshima mainland, and explanations abound for why it is used in shimauta even though it wasn’t exported from overseas. I myself still recall, being told by an elder who’d lived with shimauta culture longer than me that “falsetto is an escaping voice” although I can’t claim its veracity. I imagine that this might mean that falsetto was first used to match the pitch of the shamisen, and later to match the sound pitch of the opposing singers in call-and-response. But I have yet to prove it.

Most are songs of love and lessons

Most shimauta are love songs. When most cases of singing are call-and-response between men and women in an entertainment setting, love naturally blossomed at many such events. There were even couples who married at uta-asobi after WWII.

Scores of lesson songs were also performed. The word utahangaku is still alive in Amami, and it refers to a belief that if a person studies the lyrics of shimauta, he or she has the equivalent of half of their education complete.

Learning from stories or “rumors”

Although many other subjects are taken up in songs, I believe the story songs or what might more rightly be called “rumor” group of songs are the most characteristically Amamian. They tell of tragic women like Kantsume, Choukiku and Uratomi, the righteous Yachabou character, and females like Nabekana who appear to be goddesses.

They are the “half of an education” one can obtain from shimauta with lyrics that reveal how people lived as well as lessons to be learned that served to inform future islanders.

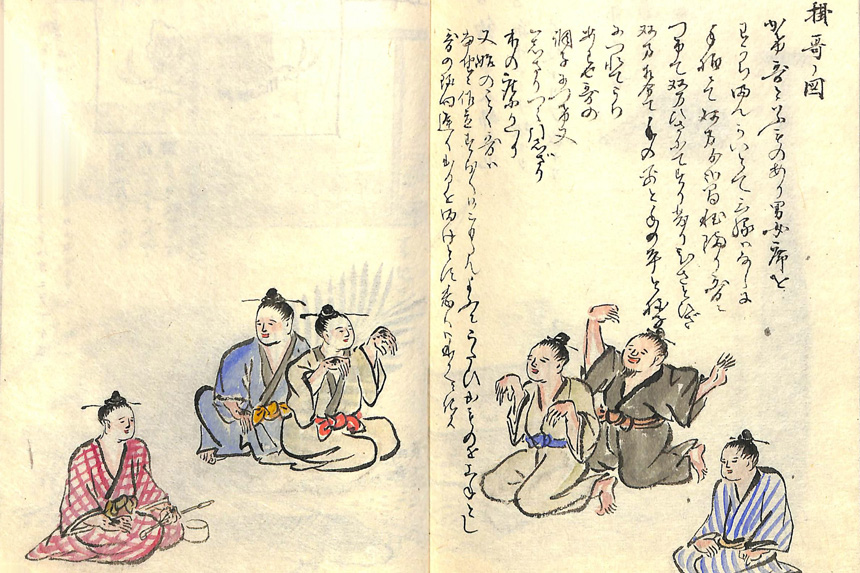

Sagenta Nagoya’s Nanto Zatsuwa, which contains illustrations and descriptions of Amami folk traditions at the end of the Edo era, depicts men and women singing shimauta in call-and-response scene entitled “Kakeuta no Zu.”

Kakeuta no Zu

Men and women separate to sing improvised songs as they keep time only with their hands, coming close together at the knees, touching palms and then returning to their spot. Since songs are off the cuff, those who can sing smoothly without pauses are lauded for their skill.

Kakeuta no Zu, Nanto Zatsuwa (Amami City Amami Museum)

Hachigatsu Odori (Amami Oshima)

Hachigatsu Odori (Amami Oshima)