Island of songs

Instrument of Shimauta, and Finger Whistle

Amami Taiko Drums

Amami chijin

The one instrument that no festival or event on Amami can be without is the taiko drum. In Amami, it’s called the chijin, and in Tokunoshima it’s the teeku.

In August according to the Chinese lunar calendar, Hachi-gatsu Odori takes place in all regions of Amami to celebrate a bountiful harvest. And it’s where the dancing, song and drums all come together as one. Several people hold the chijin and play it with a drumstick as they sing in the center of a circle of dancers. Even as early as 1850 – 1855, island life as recorded in drawings of the historical “Nanto Zatsuwa” folklore gazette show people holding chijin while dancing in a circle.

Handmade by craftsmen, the chijin is shaped like a gear. A craftsman carves a circular drum body from camphor, neem or other hardwood trees, and then stretches an unshaved horse, goat or cow hide over the top and bottom, creating an instrument rich in rustic beauty. The side of the drum is criss-crossed with cord under which curved wood wedges are inserted. A player uses a drumstick to beat the hide and produce sound.

Wedge-tightened drums have no frame: rather, the curved wedges inserted between the cord and body make the cord taut and pull the hide drum heads tight. This drum is also used on Jeju Island in South Korea, by the Yao tribes of China and Thailand, the Akha Hilltribe of Thailand, and in India.

In the past, the chijin was mostly used in religious rituals in which women were central figures. Notable remnants of this tradition live on in the villages of northern Amami Oshima, where even today, only women play the chijin. The manner of playing the drum changes based on the Hachi-gatsu Odori song, but many people say they get excited when they hear the sound of the drum.

The teeku taiko drum of Tokunoshima is twice as large as that of Amami, and produces a heavier, thicker sound with cowhide drum heads. In the Natsume Odori of Inokawa, men play the drums in an energetic rhythm of deep sounds to excite festival-goers. Cheering sections also sound teeku drums at every win or loss of a bullfight on Tokunoshima, and spectators call out “waido, waido,” waving their hands and moving their feet in ancient dances.

Women playing chijin during Hachi-gatsu Odori in northern Amami Oshima

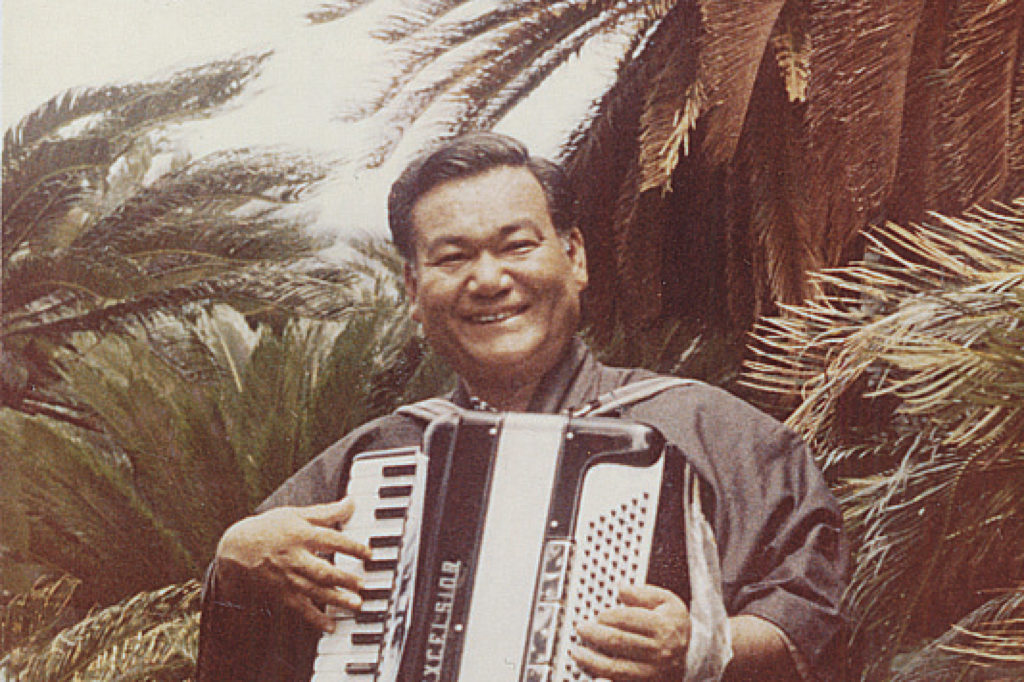

Man playing teeku during Natsume Odori in Inokawa, Tokunoshima

Amami Sanshin (shamisen lute)

The sanshin shamisen lute, essential accompaniment to shimauta (island songs) in Amami, is also known as the samusen and sanshiru. Believed to have power to ward off evil and invite wealth, the instrument is hung in living room alcoves and carefully passed down as a precious family heirloom. The sanshin is said to have come from China in the 14th and 15th centuries through Ryukyu and then to Amami. The body of the Okinawan and Amami shamisen is similar, but the ways in which they are plucked and their ranges differ and create different tones. Compared to the Okinawan version, the Amami shamisen produces a high sound with thin strings plucked both on the downward motion and the upward return. The shamisens of Okinawa, Okinoerabu-jima and Yoron-jima are plucked slowly in one direction from top to bottom, with plectrum made of water-buffalo horn.

In olden times, the body was wrapped in washi paper or Ashima silk pongee fabric sealed with a coat of banana plant juice, and in some cases even python skin was used (and it was called “samisen” because of the kanji for snake). But nowadays, most shamisen are covered in synthetic hide to protect the material and stabilize the sound. Also, the neck that is key to determining sound is made from non-lacquered ebony or rosewood. But aficionados say that if the material is good quality, you can make a neck with good feel without lacquer.

Sanshin were formerly only played by men, but now it’s common to also see women sing shame uta while playing the shamisen.

Islanders say that shima uta are best accompanied when the shamisen follows the lead of the song. Affection for the shamisen is sung in some shimauta (folk song of Amami) lyrics that give us a glimpse into the lives of ancient islanders.

Amama sanshin and bacha (bamboo plectrum)

On Yoronjima and Okinoerabujima, the Okinawan shamisen bachi is made from water-buffalo horn. The musical scale used is also the Ryukyu scale.

Amami Hato Finger Whistle

The hato finger whistle is a critical ingredient to whooping it up at Hachi-gatsu Odori or during the Roku-chou dance as well as at Amami sporting events. It takes years of skill and practice to be able to blow a finger whistle. Masters of the art say that the finger whistle requires rhythm and that you have to get the timing just right. The trick is to bend the tip of your tongue about 1 cm (0.39 inches) down into your lower jaw, and press the fingers you put in your mouth against each other in the center of the mouth. You can’t make a whistle sound when your fingers and lips are either too dry or too wet. It’s easier if you flex your abdomen muscles, set your fingers in position, and blow small amounts of air over a long time.

The traditional way to blow a finger whistle uses the little finger, but it takes a lot of practice. The finger whistle has a long history in the daily lives of the Amami people. The tone of the finger whistle is still an exceptional supporting actor at all kinds of village events.

Using the fingers to blow, the finger whistle emits a high-pitched lively sound

Photos and captions/ HORIZON Editorial Office