Essay

A Visual Journey through Akina’s Rice Cultivation Culture

In Amami Oshima, Akina is the last remaining village where rice cultivation is still taking place on the island and is linked to its well-known harvest festivals of Shochogama and Hirasemankai. This did not stop during covid times, the villagers simply closed access to outsiders but considered it important to keep the tradition going.

This article contains selected photos from Hamada’s “Mura/Village” (2001) photographic portfolio, made available to us by the photographer, which focuses on the theme of the rice cultivation cycle accompanied by his reflections and, in some cases, background information. Futoshi Hamada, an award winning Amamian visual storyteller, provides a photographic ecocultural portrait of an island community that documents with love, reverence, and care the interaction between the human inhabitants and the “more-than-human world” (Adam 1997), of this village while paying respect to the nature that contains them and provides for their multiple levels of sustenance.

As a result, Hamada leaves us with an important, albeit poignant, visual legacy. By doing so, he also documents, as an island storytelling agent, the last Amami community that still practices rice cultivation which has ensured the meaningful continuation of the harvest festivals, rich embodiments of the Amami ecocultural identity. Hamada acts, thus, as a custodian of the island’s ecocultural practices that were once a fundamental part of the Amamian life.

The visual documentation of these practices provides us with a rare glimpse into what was once an integral part of Amami’s natural, socio-cultural, and spiritual/animistic islandscape before sugarcane was imposed on the islanders by mainland Japanese agricultural interventions and impositions.

If I want to see the Amami-like village in my heart, Akina is the only village in Amami […] where rice cultivation and festivals are integrated. I realized how important 364 days were in understanding the festivals while I was doing my fieldwork. Though there are many books that explain the festivals, there is no book that talks about the everyday life of the people. (Hamada 2001, 157)

While his original intention was to document the harvest festivals, he quickly realized that these culturally embodied manifestations of the island’s identity were linked to rice cultivation and the village’s annual life cycle.

Because of the policy of reducing acreage under cultivation since the late 1960s, many farmers converted from rice to sugar cane. Before that, rice fields were everywhere. The reason why Akina Village didn’t stop rice cultivation was in the idea that you cannot stop what you inherited from your parents. They might have thought that they cannot stop rice cultivation because of these festivals, or that they cannot stop the festivals because of rice cultivation. I wish I could express the village in a way that you can imagine what is in the hearts of the villagers. (Hamada 2001, 160)

He spent several years returning to Akina to document all these aspects of the community, a commitment that can only come from a deep sense of responsibility towards his island ecocultural heritage.

I came to think that I could not feel the villagers if I don’t do rice farming myself. Therefore, I decided to cultivate rice in 1997. I felt like I was able to unite my heart to the village people by cultivating rice. I could now know how hard it was. (Hamada 2001, 154-155)

Hamada’s photos reflect his interpretation of Akina through the lens of a shared island ecocultural identity, where the natural and the cultural have long co-existed in a symbiotic manner. It is worth noting here that the Amami Islands’ ecological footprint is of substantial importance given that they are now recognized as a UNESCO Natural Heritage site along with their fellow Ryukyu Islands in the south. The Akina community and its photographer thus sit in a deeply rich ecological island context.

In his visual presentation of Akina with all its elements and their container of nature, Hamada comes closer to oral storytelling by turning the oral into visual while making little or no attempt to describe it or analyze it through words. His original Mura work had indeed very little text. Communicative meaning is affective as David Abram is quoted saying; it resonates with the landscape, and as we will see below, Hamada’s visual storytelling resonates with the island landscape that he grew up in.

“A Village of All Creation”

Akina Village is located in the northern part of Amami Ōshima, the biggest of these islands, with a port on the north side facing the East China Sea and a small hill surround- ing paddy fields on the south side. The village is one of 18 that make up Tatsugo Town in an area that is mostly occupied by mountains with little flat land (Editing Committee of Tatsugo Town 1988, 45–46). Following the depopulation trend on these islands, Akina in 2019 contained just 362 people with 215 households (Tatsugo Town Hall). In comparison, the population was at its peak in 1984 with 1,479 inhabitants and 341 households (Editing Committee of Tatsugo Town 1988, 127–128).

Akina consists of three communities: Sato at the mountain skirt on the west side of the village, Agare on the east side, and Kaneku on the northern sea side. The Akina and Yamada rivers flow through the village and into a sea of coral reefs. One of the best paddy fields on Amami Ōshima spreads in the downstream area of these two rivers.

The village has attracted a lot of folklore attention over the years because it maintains the old rice cultivation and harvest rituals that invite rice spirits to receive their thanks and are preliminary celebrations for a good harvest. The Shochogama and Hirasemankai festivals, held every year in August of the lunar calendar, were designated as important intangible cultural properties in 1985.

FIGURE 1. Aerial view of Akina Village (provided by Futoshi Hamada).

FIGURE 1. Aerial view of Akina Village (provided by Futoshi Hamada).

In the aerial image of the village, we can distinguish the sato, satoumi, and satoyama system that is so typical in these Japanese islands. While sato represents the flat, inhabited and common-use spaces as well as the arable land, satoyama points to the mountainous area right behind the sato, with satoumi demarcating the seashore that faces the sato (Nishimura 2016, 43).

Satoyama is an area where the environment has been maintained through various human efforts such as agriculture, forestry, and so on. It is a familiar area of nature created by human activities, a mountain where there is an ecosystem influenced by humans as a result of being adjacent to human settlements, a nature that has supported traditional living, or a nature created by human involvement. In satoyama, there is a model in which humans and nature coexist, a mechanism that does not deplete resources; a model of a sustainable society. In order to perform the Shochogama ritual, you need woods and rice straw to build a single roof hut (lean-to) called a Shochogama. In Akina Village, forest and paddy fields are maintained and managed so the villagers can get these natural materials to build the hut. In Akina Village, satoyama is maintained in order to perform the ritual.

An equally important element of Amami Village life has been social reciprocity. Yui is a manifestation of reciprocal relationships and is interwoven into the island communities’ social organization seen in such expressions as “lend yui ” and “return yui ” (Yamamoto 2001, 754). The villagers voluntarily unite and work together in rice fields during planting and harvesting, re-thatching of straw roofs, and rituals and festivals, as we will see in some of the photos taken by Hamada (Nakatani 2013, 54).

Rice Cultivation in Akina

Rice field in the middle, a village is stuck to it. You could say that we live at the foot of the mountain to keep the rice fields alive. Forest, river, village and sea are all connected by water, and this has continued endlessly. (Hamada 2001, 154)

Our social and cultural lenses shape the way we see and relate to each other and the rest of the planet. But our identities have not only social and cultural foundations and ramifications, but ecological ones as well. (Milstein in Knight 2020)

It is important to understand what happened to the rice ecocultural practices of these islands and why Akina’s role has been so significant in maintaining them. After the Amami Islands came under the control of the Satsuma Domain in 1609, the much higher price of brown sugar compared to rice led Satsuma to change the tax payment from rice to brown sugar in 1747. This resulted in the expansion of sugarcane fields. However, as sugarcane could only be cultivated on dry land, rice cultivation survived in wetlands, especially as some of the harvested rice was used for the important ritual of Noro.

In order to monopolize profits, the Satsuma Domain introduced a brown sugar monopoly system in 1777, making large profits as a result. In 1830, the monopoly system became even more stringent (Naze-shishi Hensan Iinkai Hen 1968, 359–365). And when the policy of reducing acreage under cultivation became enforced in the late 1960s, many farmers converted from rice to sugarcane, so you could say that rice cultivation in the islands became the victim of sugarcane, and along with it, a host of ecocultural practices disappeared or lost their meaningful connection to the daily life of island inhabitants.

Planting and Harvesting

FIGURE 2. “The soil gets fragrant”: open burning in early spring; grass becomes ash and nourishes the soil, Jan. 1997.

FIGURE 2. “The soil gets fragrant”: open burning in early spring; grass becomes ash and nourishes the soil, Jan. 1997.

In the paddy fields that have been resting since autumn, weeds are cut and burned, and then paddy field raising begins from mid-January. This picture was taken in an afternoon of mid- January when I happened to come across an opening. . . in Akina Village. The silhouette of the woman doing an open burning happened to be the mother of my alumnus. After harvesting rice in July and August, if the rice is left as it is, a second ear will sprout around September or October, which is called nakabo in Amami and hikobae (basal shoot) on the mainland. After harvesting the second ear, the rice field is left as it is, and the grass grows wild. Then, the grass is mowed and burned again. Rice planting starts around the end of March. January is the time to prepare for rice planting. The grass is mowed in the paddy fields with a mower and burned in the open, and the ash becomes fertilizer. In each rice field, an open burning was done to prepare for rice planting. When I took this picture, I intended to dynamically take the soft volumes of the smoke. Because I focused on smoke in an attempt to express the texture and strength of the smoke, the person became a silhouette. Because rice production starts from here, this photo has a profound feeling. . . . It’s wintertime, so the sun is falling south and it’s backlit. The cut grass is still blue, so it contains a lot of water, and there is no flame but a lot of smoke. The woman is burning grass . . . with a stick. Open burning is not fixed as a woman’s work. It is done by every rice field owner. While in rice planting and harvesting, labor is lent and borrowed without using money, which is called yuiwaku; open burning and the preparation are done by the owners themselves. . . . I intended to show the seasonal change by the title “The soil gets fragrant.” (Hamada 2001, 1)

FIGURE 4. “Seed paddy soaked in water sprouts” Feb. 1997.

FIGURE 4. “Seed paddy soaked in water sprouts” Feb. 1997.

Some of the rice harvested the previous year is set aside for seeding, and the seed paddy is soaked in water to germinate. The work to make a nursery and to put water in the paddy field and stir it is done in parallel. . . . I went to Akina to take photos of the festivals every year, but around 1992, I began to notice that if you only take pictures of festivals, it won’t be enough to make a photobook. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 5. The paddy fields of Akina are a valuable feeding ground for grey-faced buzzards spending the winter in Amami, Feb. 1997.

FIGURE 5. The paddy fields of Akina are a valuable feeding ground for grey-faced buzzards spending the winter in Amami, Feb. 1997.

Migratory birds such as the grey-faced buzzard flying to the islands to see the winter through know that insects sleeping in the soil would wake up and start gathering and working around the rice fields. I knew grey-faced buzzards. . . from my childhood. Akina Village attracted many kinds of birds because of the rice fields. . . . There used to be a lot of loach and diving beetle in the paddy fields, but now no more because of pesticides. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

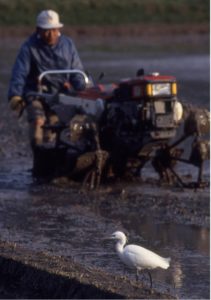

FIGURE 6. Egrets know that insects are awakened by rice paddy ploughing, Feb. 1997.

FIGURE 6. Egrets know that insects are awakened by rice paddy ploughing, Feb. 1997.

FIGURE 7. Smoothing the paddy fields manually using a wood plank, April 1996.

FIGURE 7. Smoothing the paddy fields manually using a wood plank, April 1996.

FIGURE 8. Sowing the paddy with seeds on a cool rice nursery that will become seedlings in about 30 days in a cool nursery seed paddy, March 1997.

FIGURE 8. Sowing the paddy with seeds on a cool rice nursery that will become seedlings in about 30 days in a cool nursery seed paddy, March 1997.

Sowing the seeds on a seedbed and growing seedlings until hand-planting size is different to machine planting, which results in much shorter seedlings.

When I was taking photos of Akina people, I was disliked at first. It took about two years before they behaved naturally in front of my camera. I asked permission from a village head, and when my seriousness was understood, I was first accepted by him and later by the villagers. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 9. Seedlings growing beautifully in early April 1998.

FIGURE 9. Seedlings growing beautifully in early April 1998.

To prevent seedlings from being eaten by wild birds, a net is put up on the seedlings as a protective measure. Around the time from the end of March to early April, it’s been raining almost nonstop. This time is the most suitable for rice planting, and villagers help plant each other’s rice seedlings through lending and borrowing labor called yuiwaku. (Authors’ inter- view with Hamada)

FIGURE 10. Seedlings with family, April 1998.

FIGURE 10. Seedlings with family, April 1998.

Around this time, it has been continuously raining since the end of March. . . . In my child- hood, we were asked to help with rice planting. Until seedlings take root, we need rainfall. As the work under the scorching sun gets tiring, it’s easier to work in the rain. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 11. Carrying seedlings in a cart, April 2000. 25

FIGURE 11. Carrying seedlings in a cart, April 2000. 25

FIGURE 12. “Rice planting was hard but fun,” Ms. Masu laughed happily, April 1995.

FIGURE 12. “Rice planting was hard but fun,” Ms. Masu laughed happily, April 1995.

Ms. Masu is Ms. Masu TABATA. She is the one who faithfully follows what her father-in-law has taught her. Since the Takakura storehouse behind the trees was demolished in 1995, we can no longer see this kind of scene now. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

In the old days, there was no choice but to read nature. The village people have orally passed down the experience of their ancestors for generations. For example, the old woman who appears here learned and has stubbornly followed the customs of the house from her father- in-law, who was the head of his family when she came as bride of his son. However, she said that this would be over for them. They have a great sense of crisis that such accumulation of experience would be lost. What I can do as a photographer is to leave it for posterity in the form of a photo book. (Hamada 2001, 155)

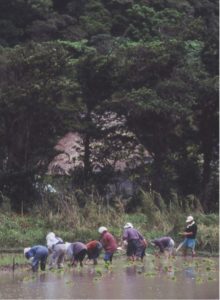

FIGURE 13. Pinch 4 or 5 seedlings and plant them at regular intervals, April 1996.

FIGURE 13. Pinch 4 or 5 seedlings and plant them at regular intervals, April 1996.

Stretch the rope and line up in an orderly manner to plant rice. The rope is wrapped around stakes on both sides and shifted little by little. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 14. The work proceeded silently in a thunderstorm, April 1996.

FIGURE 14. The work proceeded silently in a thunderstorm, April 1996.

This photo was taken during a thunderstorm. Rice seedlings are planted in a neat arrangement. Eleven people were transplanting rice seedlings. Even if you wear a raincoat, you get wet, still not so tiring compared to working under the scorching sun. Those who finished earlier take a rest while waiting for the others to finish.

The bundles of seedlings were scattered in advance. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 15. Rain during the time for rice planting is best for seedlings to grow, April 1994.

FIGURE 15. Rain during the time for rice planting is best for seedlings to grow, April 1994.

It rains a lot from late March to April, which is suitable for rice planting. Rice harvesting ends before the typhoons arrive. Rice planting and harvesting are done by reading the area’s nature well. (Hamada 2001, 156)

The long rain from late March to early April, when the rapeseed blossoms bloom, is called “rapeseed rainy season.”

FIGURE 16. “Eating lunch on the ridge is delicious,” April 1996.

FIGURE 16. “Eating lunch on the ridge is delicious,” April 1996.

The women in the family of the paddy field owner prepare the lunch before noon and bring it to eat together. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 17. The sound of the cultivator echoes in the fresh, green mountain, April 1995. 30

FIGURE 17. The sound of the cultivator echoes in the fresh, green mountain, April 1995. 30

FIGURE 18. Carrying seedlings; paddy ridges are slippery, April 1996.

FIGURE 18. Carrying seedlings; paddy ridges are slippery, April 1996.

Paddy ridges are maintained every year. The grass on the ridges is shaved off with a hoe, and then the mud from the paddy field is scooped up with a hoe and rubbed against the ridges to repair them. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 19. Migratory bird looking for food among growing seedlings, April 1995.

FIGURE 19. Migratory bird looking for food among growing seedlings, April 1995.

In this village that faces nature, one of the teachings that the elderly people have cherished is the idea that instead of doing whatever we want with nature, we need to be self-regulating. (Hamada 2001, 159)

FIGURE 20. Akina Village’s paddy fields just planted, April 1995.

FIGURE 20. Akina Village’s paddy fields just planted, April 1995.

The paddy field is a contact zone between nature and humans. The village itself is also a contact zone of nature and humans. Insects and wild birds often become protagonists. While the paddy field is the one that always goes back and forth between the animal and human sides, the interesting part of the village is that it gives them a place to take turns in their lead- ing role. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 21. Growing rice, May 1994.

FIGURE 21. Growing rice, May 1994.

FIGURE 22. The rethatching work on Takakura storehouse is very rarely practiced now, March 1995.

FIGURE 22. The rethatching work on Takakura storehouse is very rarely practiced now, March 1995.

Takakura Storehouse is assembled with only wood, bamboo, and thatch, and no nails are used. The Takakura storehouse is a gem of the wisdom of our predecessors. (Hamada 2001, 9)

Many private houses used to have thatched roofs. Each house has its roof rethatched every few years. . . . This work eventually leads to the Shochogama festival. In this festival, the important point is not on the festival day, but on the preparation itself before the festival, that is, the technical tradition of thatched roofing. This festival also has the role of handing down the technology to the young people. Since this is a difficult task and thatched roofs are vulnerable to typhoons, . . . storehouses are disappearing steadily. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 23. Wrapping a straw rope around the leg and stepping on it with full power to tighten the thatch, March 1995.

FIGURE 23. Wrapping a straw rope around the leg and stepping on it with full power to tighten the thatch, March 1995.

FIGURE 24. “Offering peach twigs and mugwort at a coral-rock tomb,” April 1996.

FIGURE 24. “Offering peach twigs and mugwort at a coral-rock tomb,” April 1996.

March 3 of the lunar calendar, which is April of the new calendar, is the festival of peaches. By this time, rice planting is almost finished. Villagers rest their bodies and go clamming at the sea on this day. On the spring tide day, coral reefs appear on the surface of the sea. Vil- lagers catch shellfish and fish in the gaps between corals and rocks. In the old days, village people were mostly poor, so they used to take coral rocks from the sea and use them as tomb- stones. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 25. “If you don’t go out to the sea on March 3, you will become an owl,” an old woman said with a laugh, April 1995.

FIGURE 25. “If you don’t go out to the sea on March 3, you will become an owl,” an old woman said with a laugh, April 1995.

According to Hamada, March 3 of the lunar calendar is a women’s festival, and it is the day of the spring tide. On that day, people used to go to the sea and purify themselves by soaking in seawater and pray for their health. Even now, the custom of praying for good health for newborn babies by immersing their feet in seawater on March 3 of the lunar calendar is practiced. Owls (crows in some areas) are considered spooky or evil.

FIGURE 26. On the biggest tide day of the year, beautiful coral reefs appear on the surface of the sea, May 1995.

FIGURE 26. On the biggest tide day of the year, beautiful coral reefs appear on the surface of the sea, May 1995.

The village is the point of contact with not only the forest but also the sea through the river. The village is thus seen as being at an intermediate point between these natural elements. Amamians followed the Ryukyuan tradition of the Neriya Kanaya and practiced the ritual of praying for a good harvest by inviting the god from beyond the sea. This is the faith in the sea. The blessings of the rich sea also moisten the village. (Hamada 2001, 158)

FIGURE 27. Ryukyu keelback looking for food, May 1995. (Less toxic than the feared habu, it prefers to eat frogs and lizards.)

FIGURE 27. Ryukyu keelback looking for food, May 1995. (Less toxic than the feared habu, it prefers to eat frogs and lizards.)

FIGURE 28. Lycaenidae sucking the nectar of violet wood-sorrel on the footpath between rice fields, May 1995.

FIGURE 28. Lycaenidae sucking the nectar of violet wood-sorrel on the footpath between rice fields, May 1995.

FIGURE 29. The ruddy kingfisher was here again this year and cried out, announcing an early summer, May 1997.

FIGURE 29. The ruddy kingfisher was here again this year and cried out, announcing an early summer, May 1997.

The ruddy kingfisher is a summer bird that flies from Southeast Asia to the islands for breeding. It is called kukkaru in Amami, and it tweets in the morning from spring to summer. The ruddy kingfisher often became the painting subject of Isson Tanaka, a famous Japanese painter of Amami Island’s natural world.2 (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 30. Welcoming the spirits, July 1995.

FIGURE 30. Welcoming the spirits, July 1995.

In an era when typhoons couldn’t be predicted and you could only read the wind, I think that people would have felt the powerlessness of humans. In those times, there would be no choice but to pray to ancestors who have returned to nature. There are wishes and gratitude in the prayers. And I feel the greatness of the soil because it gives us a harvest from where there was nothing. (Hamada 2001, 158)

FIGURE 31. Harvesting, July 1996.

FIGURE 31. Harvesting, July 1996.

Though the festivals and rice cultivation are integrated, if rice cultivation is gone and only the festivals remain, the village would gradually lose its energy. Therefore, I want them to continue rice cultivation even as a learning opportunity for children. The villagers have built a community by lending and borrowing labor called Yuiwaku or Yui from way back. I want the children to learn such a system too. (Hamada 2001, 158)

FIGURE 32. A face full of joy of a good harvest, July 1997.

FIGURE 32. A face full of joy of a good harvest, July 1997.

Mr. Tsuchiyama carrying ripe rice plants. Rice cultivation, which started with preparing rice fields in mid-January, finally reaches the harvest, being grown with great care until the harvest in July. The result is the outcome of climate and efforts such as daily management. This year’s result appeared in his smiling face. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 33. Children helping with harvest, July 1996.

FIGURE 33. Children helping with harvest, July 1996.

Everyone has memories of coming into contact with rice fields and nature as a child, and that is my starting point. I think that we have nurtured creativity by getting in touch with nature. The very place was a rice field. (Authors’ interview with Hamada)

FIGURE 34. Drying rice, July 1995.

FIGURE 34. Drying rice, July 1995.

FIGURE 35. Carrying dried rice stalks, July 1996

FIGURE 35. Carrying dried rice stalks, July 1996

FIGURE 36. Threshing together, July 1996.

FIGURE 36. Threshing together, July 1996.

FIGURE 37. New harvest, July 1995.

FIGURE 37. New harvest, July 1995.

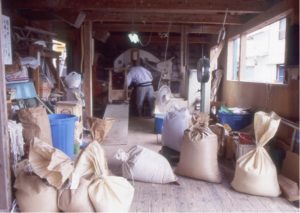

FIGURE 38. At the village rice mill, August 1999.

FIGURE 38. At the village rice mill, August 1999.

Futoshi Hamada brings an island ecocultural identity lens that serves as a reminder that ecological dimensions are inseparable from sociocultural dimensions of selfhood. This lens helps viewers visualize the crossing culturally constructed borders that separate human, flora, fauna, and environment.

Hamada’s photography shows us a community where neither the human nor nature dominate over the other but co-exist with mutual acknowledgement of each other through various layers of co-presencing and interaction. In this case, the place is a small community on a small island in the south of the Japanese archipelago and of a larger ocean. The communicative ecology of this place is not only intimately connected to but also irrevocably shaped by its islandness.

** The authors and Horizon are grateful for receiving permission to reproduce part of the original photo essay published in The Okinawan Journal of Island Studies (March 2022/2: 11-64) with the title, “Akina: An Ecocultural Portrait of an Island Community through the Photographic Lens of Futoshi Hamada” (http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12000/48047)

For the other half of the original article focusing on the harvest festivals published by Horizon see here https://amami-horizon.com/en/journal/essay/the-akina-village-harvest-festival

Sources:

Abram, David. 1997. “Waking Our Animal Senses.” Wild Earth Journal. https://wildethics.org/essay/ waking-our-animal-senses/.

Editing Committee of Tatsugo Town Monograph (1988).

Hamada, Futoshi. 2001. Mura: Amami-Neriyakana no Hitobito [The Village: Amami, the people of Neriyakana], Kagoshima: Minaminihon-shinbunsha.

Milstein, Tema, and José Castro-Sotomayor, eds. 2020. Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity. London: Routledge.

Nakatani, Sumie. 2013. “A Guide for the Study of Kinship and Social Organization in the Amami Islands.” In The Islands of Kagoshima, edited by Kei Kawai, Ryuta Terada, and Sueo Kuwahara, 54–58. Tokyo: Hokutoshobo.

Naze-shishi Hensan Iinkai Hen. 1968. Naze-Shishi Joukan Joukan [Monograph of Naze City] 1: 359–365. Kagoshima: Naze Shiyakusho.

Nishimura, Satoru. 2016. “A Study of the Public Square in Amami-Oshima: The Co-evolution of the Myar and the People.” In The Amami Islands: Culture, Society, Industry and Nature, edited by Kei Kawai, Ryuta Terada, and Sueo Kuwahara. Kagoshima: Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands: 43–49.

Tatsugo Town Hall. The population and households of the town. https://www.town.tatsugo.lg.jp/kikakukanko/chose/toke/201903syukei.html

Yamamoto, Tadamoto. 2001. Yui, In Nihon Minzoku Daijiten, edited by Ajio Fukuda, Yoriko Kanda, Hisanori Shintani, Mutsuko Nakagome, Yogi Yukawa, and Yoshio Watanabe. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Koubunkan, 754.