Interview

Futoshi Hamada

Interview with Kuwahara Sueo

Interview questions and transcript curation: Papoutsaki Evangelia

This curated transcript presents a profound conversation with Futoshi Hamada, a distinguished photographer and ecologist whose life’s work is intrinsically woven into the fabric of Amami Oshima. More than just a document of his career, this interview is a deeply personal narrative of identity, belonging, and ecological awakening.

Hamada’s story begins with a childhood shaped by the post-war era’s “dialect abolition movement,” an educational policy that instilled a sense of shame for his local heritage and a longing for the mainland. His subsequent journey—from a struggling photographer in Tokyo and Europe to his return to Amami—mirrors a larger struggle to reconcile with his roots. The pivotal moment of his life came not from a grand achievement, but from a quiet, shame-filled realization that he knew and valued little of his own homeland.

This introspection ignited a transformative mission. Through his lens, Hamada began to re-discover and champion the unique ecology of Amami, with the enigmatic Amami Black Rabbit becoming his central muse and symbol. His now-legendary 1992 poster, “Become the Wind,” did more than just win awards; it fundamentally altered the world’s perception of Amami, shifting the tourist gaze from pristine beaches to the mystical, ancient forests of Kinsakubaru.

In this interview, Hamada reflects on the complexities that followed international acclaim and UNESCO World Natural Heritage designation. He offers critical insights on sustainable tourism, the perils of overtourism, and the profound responsibility that comes with global recognition. Ultimately, his testimony is a powerful meditation on finding one’s purpose by looking inward and embracing the unique value of one’s own home, making it an essential record for anyone interested in environmental conservation, cultural identity, and the soul of Japan’s southern islands.

Where on Amami Oshima did you grow up?

I grew up until middle school in a village called En in Tatsugo Town (at the time it was Tatsugo Village). For elementary school, I went to En Elementary School, and for middle school, I attended Ryuhoku Middle School in the neighboring village of Kado. Children from Akina Elementary School, En Elementary School, and the Ankyaba village attended Ryuhoku Middle School in Kado. I walked to school every day, about 30 minutes each way.

The village population was quite large at that time. I’m not certain, but there were probably around 500 people.

When we were children, we were accustomed to seeing the events our parents participated in. This was around the 1960s, when my mother was the head of the women’s association. Kagoshima Prefecture started a campaign to “stop old customs.” In the old days, there were various events based on the lunar calendar, which meant other work couldn’t be done and efficiency was poor. So there was a push for lifestyle improvement, and it was a time when village events were rapidly disappearing.

What kind of village is your birthplace of En?

It’s a village surrounded on three sides by steep mountains with the sea in front, so there’s little farmland. My parents owned rice paddies in the neighboring village of Kado. I went there to help with rice planting and harvesting.

En village has a shallow inlet, and the beach is a pebble beach. Pandanus trees grew like a windbreak. From Ankyaba village to Akina village, we often called it “Araba” (rough wave area) because in winter the north wind was strong and rough waves crashed against the shore. En village had the strongest rough waves of all. For example, Ankyaba, Kado, and Akina have large coral reefs offshore that break up the waves and make them calmer. En has such reefs only on both sides, and waves come straight into the central part of the coast, so during typhoons and north winds, large waves still crash against the coast even today—it’s a village with harsh nature.

The village’s industries were mainly Oshima tsumugi (textile) production and fishing until around 1990. Oshima tsumugi production rode the tailwinds of the high economic growth period of the 1960s and supported the economy of the entire Amami archipelago. For fishing, pursuit fishing by free-diving, said to have been taught by Itoman fishermen, was thriving using hand-rowed boats. When I was a child, there were fishermen who did pursuit fishing from spring to autumn. There were two groups competing to catch seasonal fish.

Weaving Tsumugi

I looked forward to seeing the colorful fish when the fishing boats returned. Back then, there were many men in the village. The fishermen also worked in the tsumugi industry and I think they made a living economically. There were two general stores in the village. One was a private shop, and the other was like a village cooperative store.

Fishing

Fishing

Amami fish

What was the food life like in the village?

The food life at that time was almost self-sufficient, but that alone wasn’t enough. My mother was in the Oshima tsumugi business, so economically things improved from around 5th or 6th grade of elementary school. I think we lived normally. We could eat local fish, and almost every household raised pigs, which they butchered at year’s end, salted for preservation, and took out little by little to eat. We mainly used ingredients like island vegetables such as tsuwabuki (a type of edible plant).

My parents also grew vegetables in their home garden. Since they also had rice paddies, I don’t think we ever ran out of rice. Rice cultivation was always done, and I helped with planting and harvesting. When I was in second year of middle school, there was a policy called rice reduction, where if you converted rice paddies to fields, you’d receive money, so my parents eagerly stopped rice cultivation and eventually converted to sugarcane fields.

planting rice

Harvesting rice

In the village, there were also people called Noro priestesses and Yuta shamans. There was a summer event where new rice was offered to the Noro priestess, and those people would make miki (a fermented drink) at the Noro house and serve that miki. Back then, there were no soft drinks, so miki was for preventing summer fatigue, and my parents also made it. I remember receiving and drinking the miki made by the Noro priestesses in summer. Yuta shamans performed Maburiawase (summoning the spirits of the deceased) and fortune-telling.

Noro priestess

Noro priestess

Yuta sharman festival

Hirase mankai

Were there relatively many students at school?

My generation was after the postwar baby boom generation, but there were many students at school. One school per village. I think there were about 70-80 students in the whole school. The generation above us was the baby boom, so there were quite a few in my older sister and brother’s time. In my time, there were 15 students per grade. Now I hear there are 7-8 students in the entire school.

Futoshi Hamada in elementary school uniform

Did you speak the island dialect?

Memories related to dialect from my childhood remain as our deepest wounds.

I was born in 1953, the year the Amami archipelago returned to Japan, but from the 1960s, Japan entered a period of high economic growth, and many people from the Amami archipelago began migrating to cities seeking work. Some could only speak dialect and had experiences of being ridiculed and feeling inferior. So from the idea that children should be able to speak standard Japanese before being sent to the cities, a dialect abolition campaign was conducted in schools as an educational policy, leaving scars in our hearts.

My village didn’t have a daycare or kindergarten at the time. Growing up at home until first grade of elementary school, I lived surrounded by dialect.

When I became a first grader, there was guidance from the school to use standard Japanese, but we didn’t understand what standard Japanese actually was. For example, the word “kayui” (itchy) was “yogossa” in dialect. So when my mother asked me how to convert “yogossa” into standard Japanese, I said “yogoi,” which was completely wrong, and both parent and child laughed hard—something I still can’t forget.

At school, if you used dialect, passionate teachers would slap you or make you hang a dialect tag around your neck saying “I used dialect,” making you taste humiliation. When made to feel this way, the feeling that “I wish I hadn’t been born on this island” grew very strong in me.

So I had a strong desire to “go to the city quickly.” At home, I think it was almost entirely dialect. At school too, we spoke with friends in dialect. In other words, we were bilingual. That’s why I still remember the dialect I learned as a child. I believe regional language is like a region’s identity and soul. I still can’t understand why we were given an education that told us to discard that soul. I still wonder why education wasn’t provided saying that both dialect is important and standard Japanese is important.

What did you do during summer vacation?

During summer vacation, I mostly played in nature. There was homework, but I was so absorbed in playing that I always finished it at the last minute. I also have memories of typhoons. At that time, my house had a thatched roof, so it was very vulnerable to typhoons and suffered considerable damage, with the house getting destroyed, and sometimes heavy rain caused the river to overflow and flood.

Futoshi Hamada with his counsins

How was your connection with nature, the environment, landscape, and animals when you were a child?

In that era, I remember there being no education about our local nature—what creatures lived in Amami, what things were precious. Basically, we just followed the textbooks given by the Ministry of Education. For music too, island songs were considered old and backward, so we were made to study Ministry of Education songs and classical music in music textbooks, which is why people of my generation aren’t very good at island songs.

The only thing I remember is that a school teacher once told us that Yamato Village’s elementary and middle schools had started raising Amami rabbits. We had no idea whether there were Amam rabbits in the area around our village. Even when they were designated as Special Natural Monuments in 1963, it was taught as something not particularly relevant to us. It was an era with no environmental education about ecosystems at all.

Starting the journey of mapping Amami’s black rabbit ecosystem

Amami Black Rabbit

So you hadn’t heard stories about the Lidth’s jay either?

The Natural Monument Lidth’s jay is called “Hyosha” in dialect. They live relatively close to human settlements. Since they lived there as a matter of course, we didn’t understand their preciousness. Also, the Ryukyu robin is a Natural Monument, but because it has a very beautiful call, it was over-hunted for sale and greatly reduced at one point. For a while, we didn’t see robins around the village. White-eyes were allowed to be kept at the time, but later capturing them was prohibited. Catching them, or planting rare mountain plants in your yard, or taking things from the mountains—such thinking itself was normal in that era.

In the sea, table coral was spread out everywhere as a matter of course, so as children we’d break coral while going fishing in the sea. We completely didn’t understand how important it was because it was so commonplace to us.

Table coral

As children, we made our own toys. We’d buy a “Higonokami” folding knife and with just one knife, make spears for stabbing fish or fishing rods. We’d swim and dive in the sea in front of the village, spearing damselfish, which became meals for our parents or ourselves.

Which part of island life (culture, society, nature) remains most memorable to you?

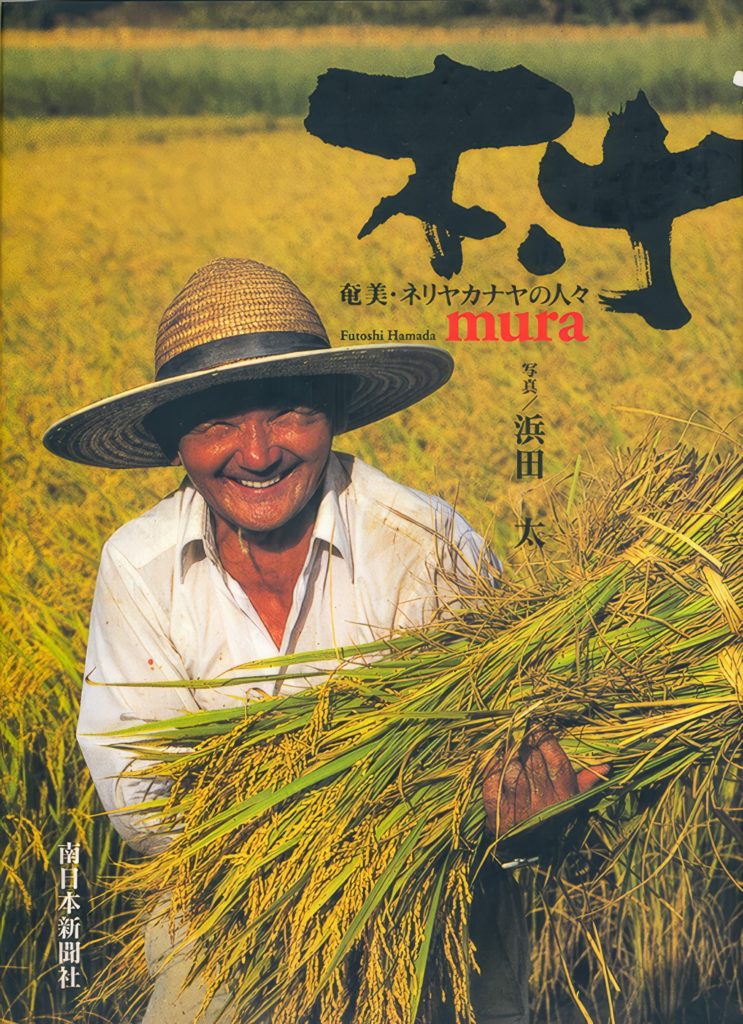

Everything. For scenery, my published work “Mura” (Village) is truly my hometown’s original landscape. I photographed in the neighboring village of Akina, but this is the hometown landscape in my heart. En village had similar scenery, so I photographed imagining the landscape in my heart. Ultimately, within one year of life, there are festivals and events throughout the day.

“Mura”: Photo collection book of the rice harvesting festivals in Akina village

For culture, in En village, there are still Hamakudari, Keiro Honen Festival, and Taneoroshi. The event I remember is Taneoroshi. In that era, it was a festival where people would perform August dances going from house to house, collecting donations for village operating funds. We ate local cuisine there. In that era, we could only eat delicious food at such times, so I remember eating a lot.

However, children’s exposure to such regional culture was also prohibited, just like the dialect abolition campaign. From around 1980, this completely changed 180 degrees to “experience your regional culture.”

Regarding nature, in spring I’d cut bamboo myself to make fishing rods and fish all the time. In summer I’d fish until typhoons came, and in autumn and winter, I’d play sword fighting in the rice paddies after harvesting, or make traps to catch migratory birds.

At that time, there was children’s association activity in the village, and what I especially remember is when children’s literature writer Mukuhato Jū, while serving as Kagoshima Prefectural Library Director, advocated a “20-minute reading campaign,” and in the children’s association we practiced having families read for 20 minutes.

Taneoroshi

Collaborative work in Mura: Burning the ground in preparation for rice planting in Akina village

Looking back at island life then, how was it?

Looking back now, I realize that island life and culture had soaked into my body, but I didn’t notice it at the time. Moreover, I was living within an educational value system that considered it old and backward, so I didn’t really understand its goodness. However, the base that makes me who I am is in these living customs here, and I think my current work is an extension of that.

Back then, various events were thriving, and villagers often did things together, so even if we were poor, we had the wisdom to do things communally according to our poverty. Unfortunately now, even in cities, nuclear families have become the norm, and traditional events are being lost and collapsing, but there are efforts to restore them—for example, even in big cities, neighborhood associations are working hard at it. However, I think it’s quite difficult to actually restore them.

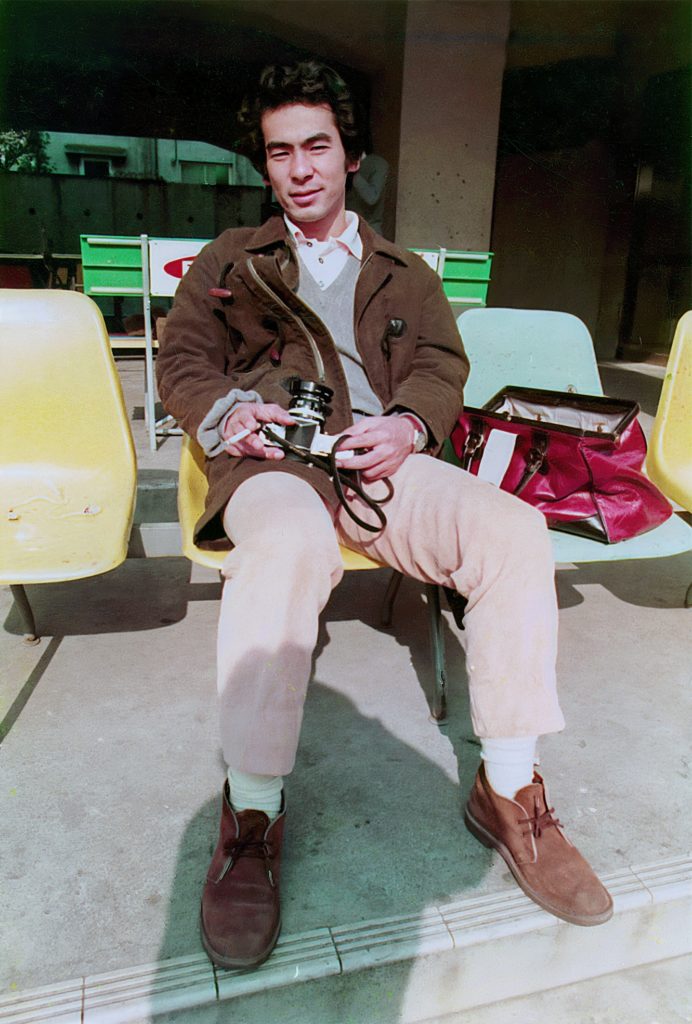

Why and how did you choose the path of photographer?

Originally, my eldest brother had opened a color photo developing and printing shop in Naze City around 1970, and as I helped out, I developed an admiration for being a cameraman, so I went to what is now Tokyo Polytechnic University and got a job as a cameraman at a publishing company. In short, it was my dream profession as a high school student.

College times

With Futoshi's mother at graduation ceremony in 1975

In my mind, cameraman and photographer are occupations with different meanings.

A cameraman properly completes commissioned photography. On the other hand, a photographer focuses on things society hasn’t noticed or has overlooked, conveys the true value of the subject in their own way, and presents it to the world. I had the commitment of the latter—a photographer. So after working for three years, I quit the publishing company and went abroad to study to become a photographer, but I failed.

When did you first awaken to being an Amami person from a small southern island of Japan?

My life as a cameraman in Tokyo failed, and I returned in 1979. However, I couldn’t quite settle on a photography theme and continued living aimlessly, but then something happened that greatly changed how I lived.

When I came back, because I had returned from the city, I was a bit conceited, but it was a time when work wasn’t going well and I was frustrated.

I was in a hotel elevator with 4-5 tourists. One of them asked me, “Where’s interesting to go in Amami?” I reflexively answered, “Is there anywhere interesting in Amami?” Then they said, “If this is what locals are like,” and when I heard that, I immediately felt ashamed and hurried back to the office. My head was filled with wondering why I’d said such a thing.

When I thought about it carefully, I had failed at city life and come back, and now I had to live in my hometown—my hometown is the stage for my life from now on. About my hometown, which would be my life’s stage, to say “Is there anywhere interesting?” was far too empty regarding my own life. From there, I questioned myself for the first time about what Amami meant to me.

Awakened by those words, I realized that until then I had been looking at my hometown’s nature, comparing Amami unfavorably to Okinawa as backward, comparing it to cities as old and backward—capturing everything negatively through comparison.

Forest in Amami

I reconsidered that everything before my eyes is Amami, not good or bad places, but accepting all of Amami. From there, how I pointed my camera changed greatly. Until then I’d been taking only ocean photos. I’d been capturing images of beautiful blue seas, blue skies, white sandy beaches, like a southern island, but I became conscious that the real Amami couldn’t be seen unless I also accepted everything I’d previously denied, which was around 1984. That doesn’t mean I immediately found a theme though.

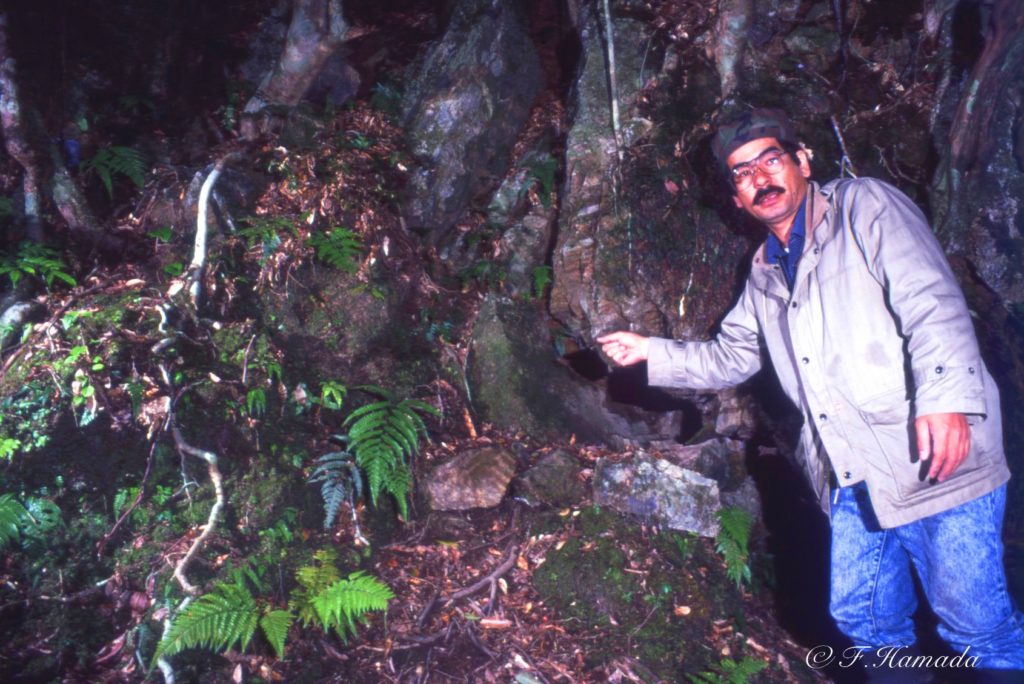

Another trigger was the visit of Prince Philip of England to Amami Oshima. In October 1984, he came especially to see the Amami black rabbit.

We only read about it in newspaper articles, but the fact that royalty from England, from the other side of the earth, would come especially to see Amami’s nature and Amami rabbits—we thought, is the Amami black rabbit really such an amazing creature? Local nature conservation activists also felt that locals should understand Amami’s nature better and established the “Association to Consider Amami’s Nature.” I wanted to see the Amami black rabbit myself, and in 1986 I saw an Amami rabbit for the first time, and from there I became absorbed with Amami rabbits.

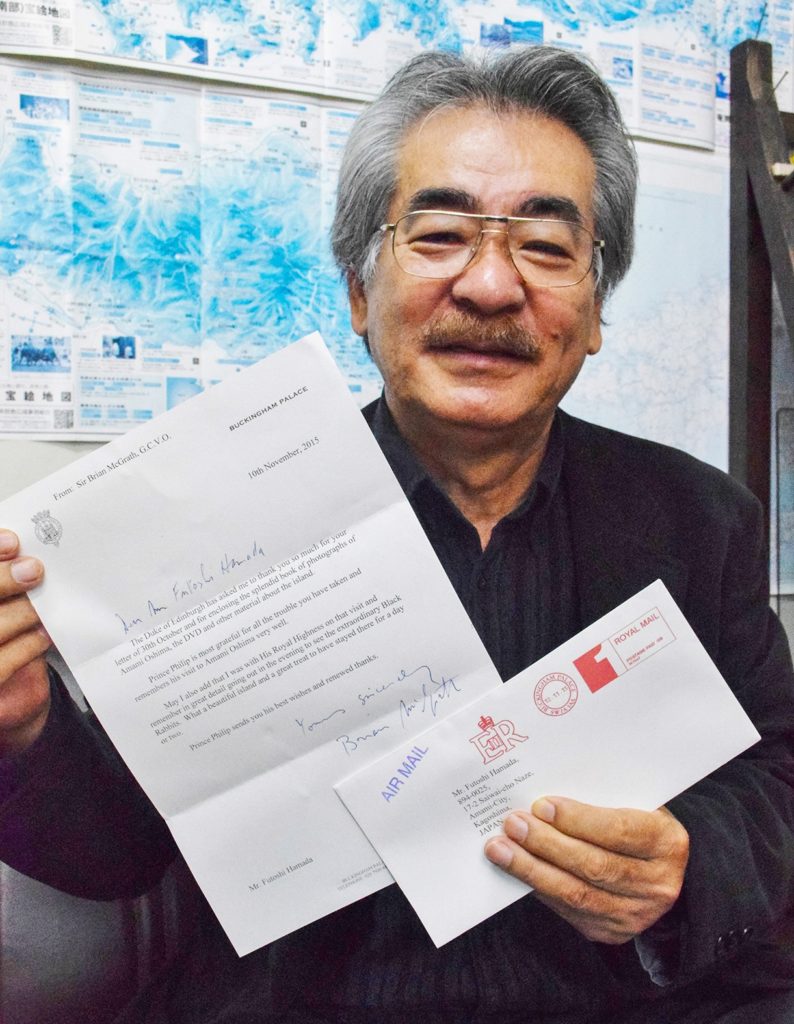

Prince Philip knew about Amami rabbits before coming to Japan, and as president of the World Wildlife Fund, the Japanese committee arranged his visit. The prince’s visit itself was amazing, and it became another turning point in my life.

As an aside, in 2015 I sent a photo book and video I’d taken directly to Buckingham Palace, and was surprised when a thank-you letter arrived immediately. It was just before his passing. The thank-you letter is displayed as a family heirloom in our home.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh’s letter.

In July 2021, Amami Oshima and Tokunoshima were registered as World Natural Heritage sites together with northern Okinawa Island and Iriomote Island, and I think Prince Philip, having seen Amami Oshima’s nature in 1984, may have predicted its World Natural Heritage value.

Through such circumstances, with two turning points in my life, I wanted to have my own theme. From what angle should I view Amami—I really wanted such a theme, and among these, the Amami rabbit is a symbol of Amami’s nature and an animal that goes back to Amami’s very origins, so at first I didn’t give it such deep meaning, but from there it gradually expanded, and looking back now, I think I established the vague goal as a photographer of “conveying the true nature of forest creatures in Amami and presenting their value to the world.”

Amami Black Rabbit

How did your work as a photographer develop after returning to the island?

Right after returning, I opened a photo studio taking commemorative photos and made a living. In summer 1986, I’ll never forget, I went with my family of four to see the sunset at Ohama Beach in Naze. Even then I was thinking about finding some theme for myself. It suddenly flashed to me that I wanted to see a Amami rabbit.

At that time, I’d heard that if you went to the Super Forest Road that runs along Amami Oshima’s ridges, you could see Amami rabbits, so I went with my family by car. We drove for about 40 minutes, and just around the Kinsakubaru virgin forest area, I saw a Amami rabbit for the first time. It was standing in the middle of the road, its eyes glowing ruby-colored, and I got goosebumps all over. From there I became possessed, wanting to take photos of Amami rabbits no matter what. Every night I threw myself into photography with complete devotion.

This is where my relationship with the Amami black rabbit began.

You’re famous for your work on Amami’s nature, especially the Amami black rabbit, but when did you start recording the Amami black rabbit? And why? What’s special about this animal, and why is it important for Amami?

Until then, photos of Amami rabbits in tourism pamphlets were only of taxidermied specimens. So I wanted to photograph natural ones. Professor Suzuki at Tokyo University’s Medical Science Research Institute had also photographed them and published them in a book with stories of his struggles, but in that era it wasn’t in color. In that era, it was such a difficult animal.

So in color photography, I was the first to photograph it. Moreover, starting from 1986, there were photos taken on roads, but I was the first to photograph in color a photo coming out of a burrow. I remember that was January 9, 1987. I got 13 photos.

Amami Black Rabbit

I found a burrow in November 1986, and through trial and error, took photos using a handmade device that triggered the shutter when the rabbit stepped on it. However, I had fear of habu vipers, so I couldn’t overcome the fear of entering the forest. But when I became absorbed, I told myself that if I didn’t do this, I’d have nothing for the rest of my life. Otherwise fear would stand in the way first and I couldn’t move forward.

Anyway, with the feeling that I had to photograph their natural appearance, I was compelled to decide to enter the forest to search for burrows. As I went deeper and deeper into the forest, I felt that without photographing both the rabbits’ everyday lives and the forest that nurtures them, I couldn’t tell their story, so I worked on both forest photography and Amami rabbit ecology.

I searched quite a bit for places where Amami rabbits frequently appeared. In that era, roads weren’t as developed as now, but I often traveled the Super Forest Road. Currently Amami rabbits appear on the old national road, but nothing like that happened back then. Moreover, the forest was full of bald mountains from logging everywhere. Just when Prince Philip visited was right in the middle of massive forest logging. He must have seen that scene. I remember a newspaper article with his words saying, “It’s important not because precious creatures live there, but because protecting the environment is important.” That was the kind of era it was. So places where Amami rabbits frequently appeared were limited. The mountains were devastated in the old days. Now, mongooses that weren’t originally there have been eradicated, the forest ecosystem has recovered to its original environment, and Amami rabbits can live in peace.

The Amami black rabbit is a living witness that tells the story of Amami’s formation. The Ryukyu Islands including Amami Oshima were connected to the Eurasian continent until about ten million years ago. From about two million years ago, they were separated from the continent, and endemic species including Amami rabbits that remain today are thought to have been left on Amami Oshima and Tokunoshima. So the Amami rabbit is a living witness that tells the story of Amami’s formation.

The Amami black rabbit is a symbol of Amami’s nature and Amami’s very identity. Protecting Amami’s nature means protecting Amami rabbits. Protecting Amami rabbits means protecting Amami’s identity.

At that time, was no one paying attention to Amami black rabbits?

There’s Tokyo University’s Medical Science Research Institute in Setouchi Town. There was someone named Professor Suzuki Hiroshi there who researched tsutsugamushi mites parasitic on Amami rabbits. This professor researched Amami rabbits not for the rabbits themselves but for tsutsugamushi research, and left behind a book called “The Island Where Amami Rabbits Live.”

Also, at Yamato Village’s elementary and middle schools, they raised Amami rabbits and compiled research results about rabbit ecology in captivity for children. People named Okamoto Fumiyoshi and Kirino Masato published books*, and I read them thoroughly and approached it, but I’m not a scholar, so it was trial and error. I’m not a wildlife photographer either, a complete amateur groping my way, but as I gradually started, I found the theme of Amami rabbits, and from there I actually began going to take photographs.

*Okamoto Fumiyoshi 1971 “Amami-no-kuro-usagi” Gakken

*Kirino Masato 1977 “Amami-no-kuro-usagi: Living Fossil” Chobunsya

What was your most impressive encounter with an Amami black rabbit?

It was definitely when I discovered and photographed a mother rabbit raising baby rabbits in a breeding burrow for the first time in the world. In 1993, I built a small hut about two tatami mats in size in the deepest part of Amami Oshima’s forest and made it my base for Amami rabbit ecology research. In November 1996, I found a Amami rabbit breeding burrow for the first time. I’d heard that mother Amami rabbits dig separate holes from their own burrows for child-rearing, but I never imagined I’d find such a burrow. For a month and a half I stayed in the forest and recorded frantically. The mother rabbit digs a breeding burrow separate from her own burrow, nurses for 2-3 minutes around 2-3 AM every two days, then carefully closes the entrance for about 20 minutes, raising the young over about 40 days. Being able to photograph this child-rearing that no one had ever seen, wrapped in a veil of mystery for ten million years, I felt the mountain god had brought me to it. They were truly dear.

Amami Black Rabbit mother with baby

What do you think is the greatest threat to the Amami black rabbit?

Road kill - Amami Black Rabbit

The greatest threat is definitely humans. Whether they live or die depends on humans, I think.

Mongooses that didn’t originally inhabit Amami Oshima were released into the forest with human shortsightedness saying they were for habu extermination, and Amami rabbits and other creatures were predated at a tremendous rate, greatly reducing their numbers. After spending enormous costs, mongooses were eradicated in 2024, and now Amami rabbits and others are recovering in numbers, but it’s not complete. Also, forest logging and development are threats. When rabbit habitats are fragmented and isolated, genetic diversity is lost and resistance to disease weakens. Traffic accidents are also a problem. Rabbits run over by cars on roads never stop.

How do you see the future of the Amami black rabbit?

Thanks to World Natural Heritage registration, I think resident awareness of nature conservation has risen considerably compared to 30 years ago. In 2024, mongoose eradication progressed and the ecosystem is recovering. Rabbit numbers are definitely increasing. But we can’t let our guard down yet. We must continue conservation activities. Also, local people’s consciousness has changed. Recognition has spread that Amami rabbits are Amami’s treasure. I want to convey the importance of Amami rabbits to children too. Through Amami rabbits, I want to pass on the wonderfulness of Amami’s nature to the next generation.

What’s your message to young people of Amami and people worldwide?

“World Natural Heritage registration wasn’t achieved in a day.”

What must never be forgotten is the activity of teachers in natural sciences, starting with Ōno Hayao, the father of Amami natural history, who conducted basic natural surveys from around 1953 when the Amami archipelago returned to Japan, including Professor Sakuda Hirotsune, Professor Shigeta Hiroo, Professor Tabata Mitsutake, and others. (Activity of Professor Ōno and others)

Mr. Ono, Mr. Shigeta Mr. Sakuta, and Mr. Tabata

The professors appealed for the importance of Amami’s globally precious nature and continued sounding warnings, but amid a development-centered industrial structure of nature destruction, they apparently received much harassment. Even so, without being intimidated, they continued surveys and warnings.

As a result, we must tell future generations forever that thanks to these professors leaving precious materials, World Natural Heritage registration was possible.

And I want people to look at their hometown anew. Hometown nature and culture have irreplaceable value. I understand the feeling of longing for city life, but hometowns also have wonderful things. I want people to realize that. And take pride in their hometown. Amami has nature and culture to be proud of to the world. Amami black rabbits are its symbol. I want people worldwide to know Amami’s wonderfulness. And participate in activities to protect Amami’s nature. Even if each person’s power is small, when everyone gathers, it becomes great power. Together, let’s protect Amami’s future.

What are the challenges that come with this international recognition? (Controlling overtourism)

What I think is that the easy approach to tourism of just having lots of people come is temporary, and shouldn’t be evaluated by numbers. For example, not whether tens of thousands came in a year being good or not coming being bad—not quantity but quality, thinking about approaches where for 50, 100, 1000 years and beyond, we grow together hand in hand with Amami’s creatures, will have benefits for generations. Tourism where only we right now are fine won’t be sustainable, I think. Because it’s fragile. In that sense, regarding what policies the administration aims for with tourism, we need to firmly establish mutual rules.

“We were once scorned with ‘Can you eat from nature?'” However, economic effects from nature guides and such are immeasurable. For example, nighttime night tours cost 8,000 yen per person. With 4-5 people that’s 40,000 yen. If done 10 days, that’s 400,000 yen. Such work never existed before.

Even during the day, it varies, but costs 4-5,000 yen. Taking about 10 people to Kinsakubaru forest, guiding alone, such business is viable. Being too greedy for more isn’t good. I think we need to establish systems.

That this became possible is greatly due to World Natural Heritage registration. Being registered as World Natural Heritage provides protection, but if we use it excessively, nature will break, so how to self-regulate is the challenge. In that sense, without self-regulation, I think Amami’s nature won’t last. That’s the overtourism problem.

Is the Amami archipelago prepared to handle overtourism? Do you think there’s capacity to cope (infrastructure, creative businesses, hospitality, etc.)?

Kinsakubaru iconic forest

Yes. For example, places like Kinsakubaru can only be entered with guides. Also, for nighttime night tours at Santaro Pass, there’s regulation that you can’t enter without applying. You can apply and get permission online, but still, in Kinsakubaru’s case you can’t enter without a guide. With a guide costs money. According to a recent newspaper, the “Association to Consider Nature” made a request saying it’s strange that even locals can’t enter without a guide. Of course entry regulation is necessary, but I think it’s strange that even local people have to pay 3,000-4,000 yen per person.

So this is a rules issue.

It’s a rules issue. During COVID, customers decreased considerably. Although it became a World Natural Heritage site, tourists didn’t come back all at once. I heard it was quite controlled. Then there are repeat visitors. High-quality tourists who come repeatedly, going to various places paying appropriate money, repeating—we need such high-quality people to come or it won’t work, I think.

As a result of UNESCO Natural Heritage, what are sustainable methods for new tourism coming to the island?

Connecting to the earlier discussion, I think without firmly grasping appropriate capacity for each place and how much is moderate, and regulating that no more can enter, it won’t work. I think it’s necessary to carefully examine tolerance capacity including with researchers.

How do you want tourists coming to Amami to see and experience the island’s culture and nature?

First, confidently introduce scenery and places to touch nature. In other words, I think it’s important that local people first firmly understand where they live. It can only start from there, can’t it? In that sense, we’re doing such education now. It’s changed quite a bit from 20 years ago.

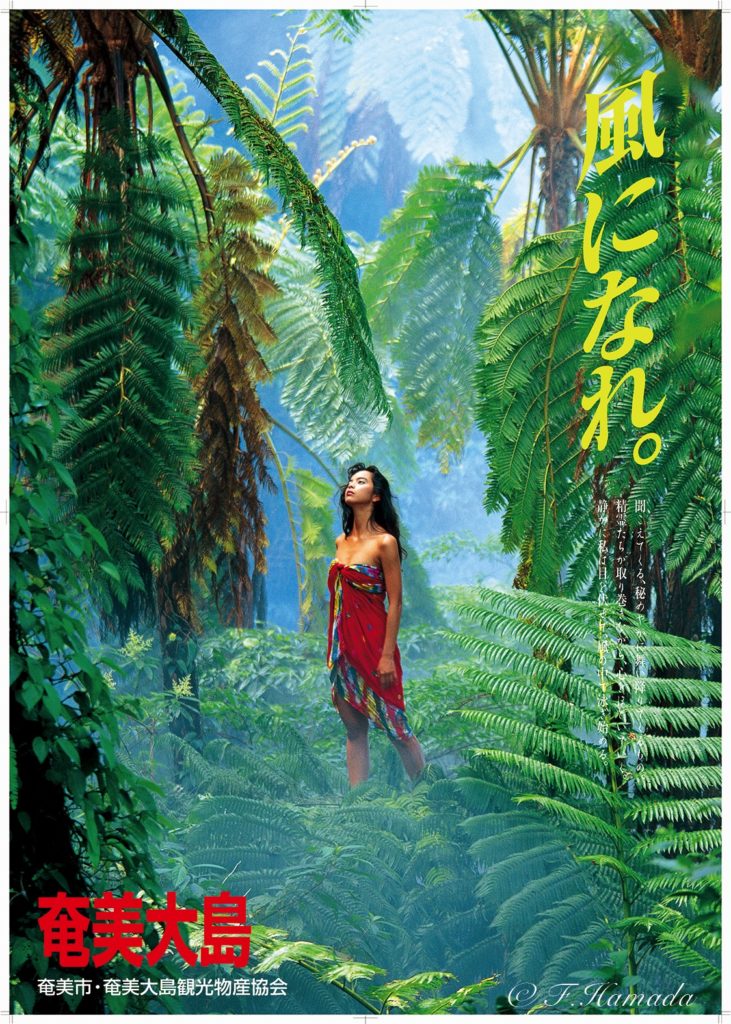

Poster "Kaze ni nare"

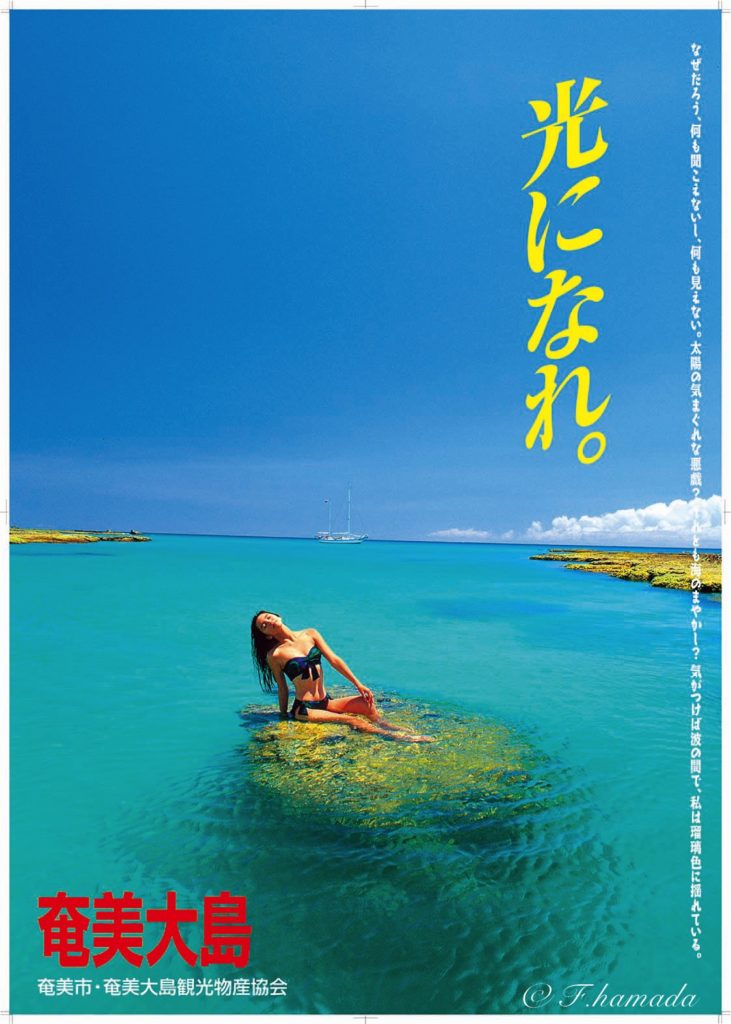

Poster "Hikari ni nare"

What about Amami do you want the world to know?

Just like the Peter Rabbit story, I want it to be an Amami Rabbit island, where such animals and humans can live happily together, living in peace, receiving those benefits—I want it to become such an island. Since we spent so much enormous money to eradicate mongooses, with Amami Rabbits living happily in Amami’s rich natural environment, while protecting their environment, I want people to know a story of human-animal coexistence where humans also join hands with them to create the future.

How important is it that Amami is introduced to outside visitors and tourists with local voices?

In terms of first taking pride in where you live, as one person’s life, realizing “I was born and raised in such a wonderful place” is extremely important when thinking about life from now on, I think. I had the experience of leaving the island without confidence, ultimately wandering and coming back, and finally here finding my way of life.

As the next step, by taking pride in one’s hometown, it holds the potential to give birth to new ideas—truly golden eggs. From there, the possibility exists for even more amazing Amami to be born. Building on past heritage and elevating it further. From the return to Japan until the 1990s, there was a fault line from rushing to urbanize. From 2021, by building up here, people with such values will come from outside, and such people may also be born locally. Then I think the island will become one with more depth and substance.

Being registered as World Natural Heritage means Amami belongs not just to Amami people but to the world—what do you think about that?

That’s exactly right, I think. We were recognized for having an ecosystem and biodiversity without parallel. Ultimately, “In exchange for recognizing that, you must properly protect it”—we bear that responsibility. We must have a sense of responsibility that we must bear the duty to protect and nurture the future. I don’t think it’s just that we receive benefits and can make a living from it.

Who should become the administrator of Amami Natural Heritage?

Each individual person, I think.

You’ve now become a visiting researcher at Kagoshima University’s Island Research Center—what are your future achievement goals? Also, why is it important for Kagoshima University to collaborate with locally active people like yourself?

Amami Black Rabbit - night forest scene

This time, I thought to request this visiting research position as a culmination for myself. Until now I’ve revealed Amami rabbit ecology in fragments, but when I first saw the observation hut in Tokunoshima’s Tobe village, there were over ten Amami rabbits in the surrounding grasslands. I was shocked. Soon after the hut was built, I stayed and looked, but at that time they weren’t around there. Not knowing so many were coming, I was shocked. Usually Amami rabbit life is in the forest, surrounded by trees, so it’s invisible. But around there, if you want to see Amami rabbits’ ordinary behavior, you can see it, so I thought by recording their behavior throughout the year, some new ecology might become visible, so I thought to install cameras and investigate.

There are about 7 burrows very nearby. Rabbits go in and out from there to the clearing, and also come from elsewhere. Now I’ve attached one camera each to all the burrow entrances and exits, recording exit and return times. The time leaving burrows and time appearing in the clearing are different. This is due to brightness, being cautious and appearing in the clearing after dark—I generally understand such things, but by investigating such things, their annual life becomes visible. And I have data that the child-rearing period is roughly November to the following May, when they move quite actively. But this is only one year, so to verify whether there’s really regularity, whether it’s certain, I’m thinking of observing for 2-3 years. When that data is collected, I think their true nature will become visible.

In my mind, if I prove all that with video and data, it might lead to new discoveries. It’s nighttime, invisible, a difficult theme, but if I try, I can do it with equipment I now have. I’d rather donate it to an important institution, teach the methods, and have the next people build on top and elucidate. Then knowledge inheritance among researchers becomes possible, I think. I’m also reaching limits physically. If I present next year, from the year after, young researchers can take over, and I hope we can develop it while passing it on.

By doing this recording at that place in Tokunoshima, I want to acknowledge what I’ve worked on and leave results. I think that’s also important.

I cannot elucidate everything in my lifetime alone. So to pass it on to the next young generation, I want the Island Research Center to inherit it, including equipment. A Amami Rabbit Museum was built in Yamato Village. There’s an observation hut. In the future, I hope research will be conducted in cooperation with such places to elucidate the individual ecology of Amami’s creatures.

This research requires tremendous patience. It would be good if it were local people, but locals don’t really have interest in it, so I don’t know what kind of people will come, but for inheritance, I think this Island Research Center must become the base. Gathering lots of information here and publishing accurate ecology. I want it to become such an information transmission base. I’m hoping people who become interested will appear.

Today’s conversation had many discoveries for me too.

Thank you very much.